Get to Know the 5 Types of Salmon

Wild Pacific salmon come in five delightful varieties. Learn the differences.

Nov 19, 2024

To the average seafood lover, all types of salmon can seem the same. After all, they may not look very different when they’ve been processed and packaged, which is how most of us encounter salmon in our daily lives. But each different species of salmon actually has a unique evolutionary history that creates distinct flavors and nutritional qualities.

If you’ve made the commitment to add salmon to your diet (an excellent idea, as it’s among the most healthful foods humans can eat), it’s worthwhile to take the next step and become a salmon connoisseur. So here’s how to find the best species for you and your family.

Meet your salmon

In North America, there are five major species of wild Pacific salmon: keta, pink, coho (silver), king, and sockeye. Another species, the masu salmon, lives in Asia.

Atlantic salmon are native only to the ocean they're named after. (The “Atlantic salmon” found in stores is farmed all around the world.)

A few species of trout are also sometimes called salmon. Steelhead, for example, also known as rainbow trout, can be referred to as salmon if they travel to the ocean after they’re born.

However, if you’re eating wild salmon in North America today, you’re probably eating one of the five major species.

These species don’t just look similar when they’re shrink-wrapped. Even when they’re living out the prime of their lives in the ocean, most salmon species look roughly similar. They have blue-green backs and silver sides, perhaps speckled with darker spots.

The big difference comes when they swim for shore. By the time salmon have returned to their ancestral breeding grounds to spawn, they’ve changed dramatically. Some species grow giant humps on their backs, and their mouths may sport a hooked upper jaw. Certain salmon turn a deep shade of red, while others become brown, or sport multicolored bars across their sides.

The life-cycle of a salmon

Salmon are anadromous, which means they transition between freshwater and saltwater. The baby salmon, or fry, hatch in gravel beds located in clear freshwater streams and grow up in rivers or lakes.

Once old enough, the mature fish swim to the ocean on a journey that can span hundreds of miles. Once in their salty new home, salmon spend anywhere from a year to several years growing and feeding on crustaceans and smaller fish. Eventually, they’ll journey back to the streams and rivers that birthed them. There, the mature fish lay and fertilize eggs, starting the ancient cycle anew.

These salmon runs happen throughout the year in the Pacific Northwest and in Alaska, and the timing varies by species. Some populations, like Chinook, see more than one migration per year. But these runs are typically when salmon fishermen make their catch, following the strict regulations set by fishery departments to ensure populations stay healthy.

Then the salmon are shipped, either fresh or frozen, to consumers across the continent. Salmon are prized by seafood lovers for their rich flavors and exceptional purity, as well as the many health benefits the fish contain. Salmon also have some of the highest levels of omega-3 fatty acids, due to their rich, healthy fat stores. And they’re packed with other essential nutrients like vitamin D, selenium, and lean protein. In addition, salmon’s characteristic pink coloration comes from an antioxidant known as astaxanthin. They get this from a diet of krill and other crustaceans in the ocean.

While all species of Pacific salmon are nutritious and sought-after by seafood lovers, there are important differences between them:

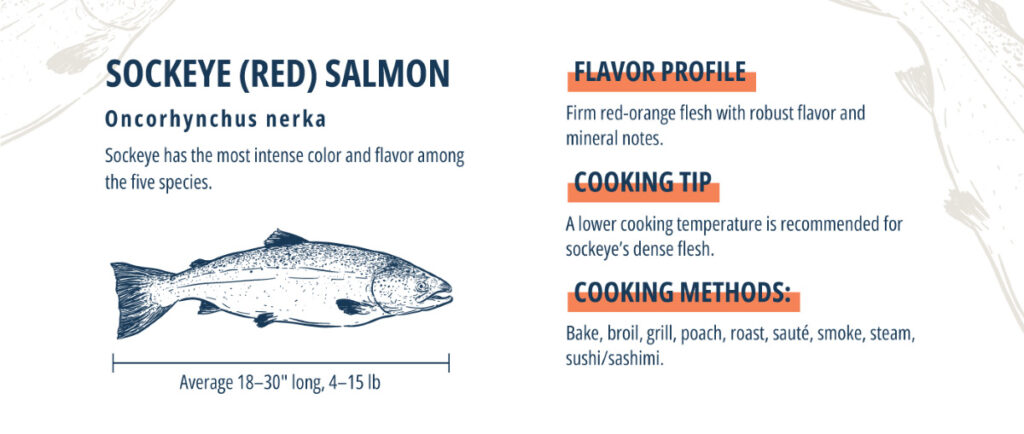

Sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka)

Sockeye salmon’s rich, savory flavor and firm texture make it one of the most desirable species for seafood lovers. Sockeye benefit from a diet high in ocean krill, which gives their flesh a rich pink coloration.

On average, sockeye live longer in freshwater than other salmon species, spending up to three years in lakes and rivers.

Sockeye salmon can be spotted during the annual run by their bright red bodies contrasted with dark green backs — changes that occur shortly before they begin spawning. There’s even a special variant of landlocked sockeye salmon called kokanee. These spend their entire lives in freshwater and never travel to the ocean. These are becoming rare, and have been declared endangered in many locations in the U.S. and Canada.

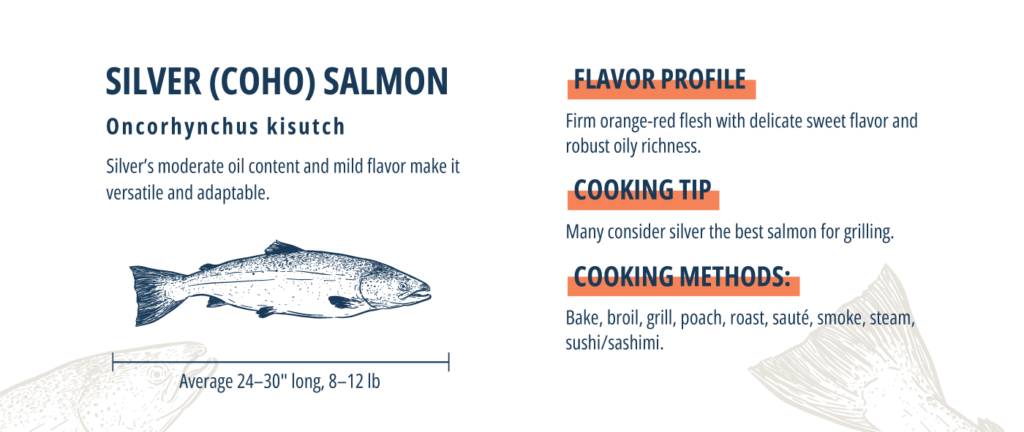

Silver salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

Though silver salmon, also called coho salmon, make up around just 10 percent of the yearly catch, they are one of the most sought-after salmon species. Their meat is delightfully moist and delicate and is ideal for grilling. Their sides are bright silver in their ocean phase. Like sockeye salmon, they have bright red sides and dark green backs when spawning.

Silver salmon usually don’t travel far to spawn. They’re typically the last to travel upstream in late fall and winter. While they’re leaner than other salmon, they still pack in a hearty serving of omega-3 fats: almost 1,500 milligrams per 3.5 ounces serving, according to the USDA. Vital Choice’s Silver salmon are line-caught on small boats, iced immediately, and flash-frozen within a few hours of leaving the water.

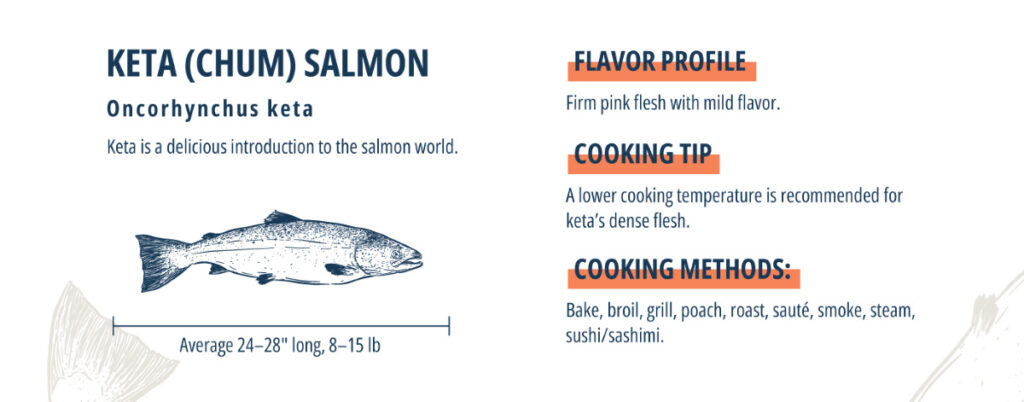

Keta salmon (Oncorhynchus keta)

Keta, or chum salmon, are the most widespread population of salmon, found in the Pacific waters from San Diego to South Korea. They travel far upstream to spawn, taking rivers from the ocean deep into the heart of Alaska and Canada. When traveling upstream to mate, they bear stripes of red, yellow, and purple on their sides.

Keta salmon are leaner and milder than most species, and they have a wide variety of unique flavor profiles. Vital Choice’s keta salmon come from pristine, frigid Alaskan waters, where they’ve been a foundational aspect of indigenous life for generations.

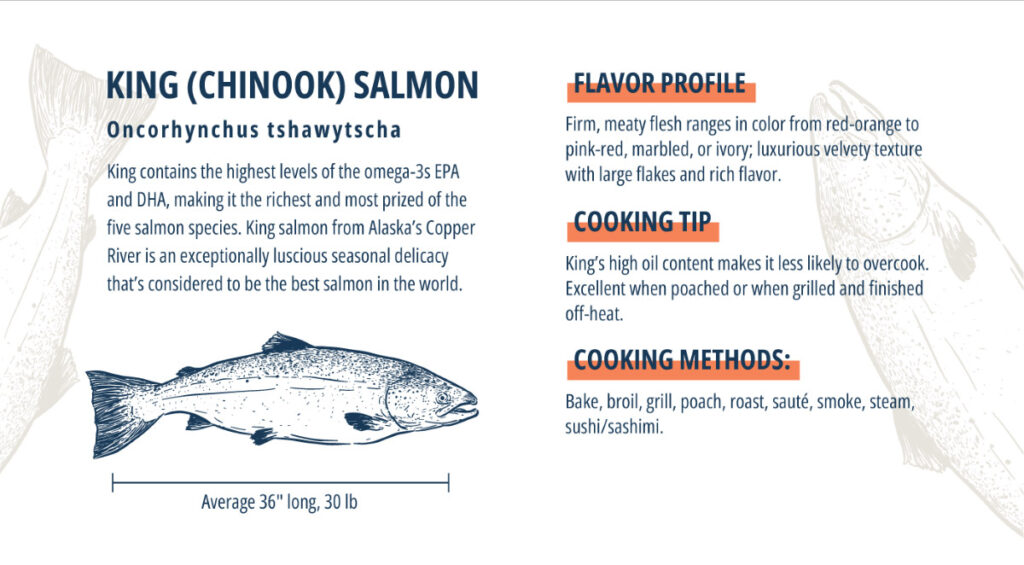

King salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

King salmon, also called Chinook, are the largest, but least abundant species of wild salmon. Appropriate to their royal name, they pack the most omega-3 of any salmon species. The extra fat adds a smooth, almost buttery quality that makes the king prized by many seafood lovers.

King salmon can measure almost five feet long and some weigh over 100 pounds, but they’re more commonly caught at around three feet long and 30 pounds.

King salmon are found throughout the West Coast, from Alaska all the way down to California. There are multiple runs of king salmon every year, each involving a distinct population. These salmon turn brown when they enter freshwater to spawn, making them easily distinguishable from other salmon species.

Though their populations may be smaller than other salmon species, the king salmon that Vital Choice harvests in Alaskan waters benefit from the best population management on the planet. Strict regulations created by a coalition of policymakers and scientists ensure that salmon populations thrive from year to year while satisfying seafood-hungry customers everywhere.

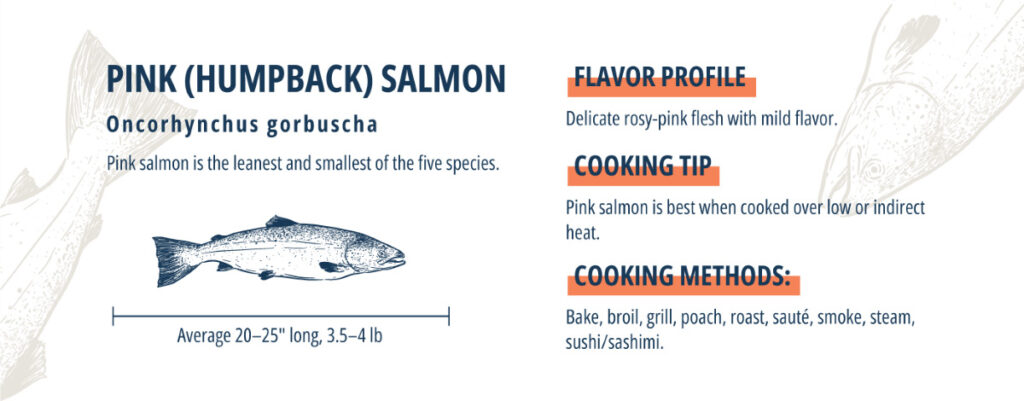

Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha)

Pink salmon are the smallest and most abundant species of Pacific salmon. They’re often called humpies because of the large hump that grows behind the males’ heads during spawning season. The humpies’ mild flavor, soft texture, and relative lack of fat make it a good fish to pair with citrus slices or top with butter – or both!

Pink salmon spawn in two-year cycles near the mouths of freshwater streams. This pattern results in predictable, genetically distinct even- and odd-year populations of pink salmon. They also typically travel the shortest distance to spawn, as they like to mate where rivers meet the ocean.

So, experiment with the variety of wild salmon choices that nature — and Vital Choice — offers. The extraordinary tastes and textures you encounter may well lead you to a new favorite!

Photos courtesy of Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute