Lobster Facts: A Cinderella Story

Lobster facts may surprise you. These crustaceans were once food for the poor. How did they become a delicacy?

Jun 07, 2022

Lobster, now synonymous with fine dining, didn't always have an upscale reputation. It's hard to believe today, but beginning in colonial America, lobster was once a low-status food.

Its story demonstrates that humans prize that which is “hard to get." When lobster meat was abundant, the average American somehow regarded it as less delicious. When it became scarce, we craved it.

It is a Cinderella tale, of a sweet pink-complexioned meat that to us seems intrinsically superior, yet was not appreciated...until it was.

Lobsters...lobsters everywhere...

When the Pilgrims arrived on these shores, the people who lived here used lobster meat as fertilizer and bait. Anyone could wade out into a bay or estuary, reach down, and snatch a large lobster weighing as much as 25 pounds. After a hard storm, lobsters might litter the shore in piles two feet tall.

The same was true in what's now Canada. On visiting Newfoundland, the historian William Wood wrote of lobster: "Their plenty makes them little esteemed and seldom eaten." Native Americans preferred other seafood, ideally bass. When they did eat lobster, they covered the carcasses with seaweed and baked them over hot rocks — perhaps the inspiration for the New England clambake.

Lobster was the food of last resort for the new settlers, more available even than bread. In 1622, Governor William Bradford of the Plymouth Plantation apologized to guests that the only dish he "could presente their friends with was a lobster...without bread or anything els but a cupp of fair water."

This was not true worldwide. Back in England and Europe, the wealthy served lobster for elegant dinners. We can see in a record from the British diarist Samuel Pepys that in 1663, he served four lobsters at a dinner he hosted (along with fricassee of rabbit and chickens, carp, lamb, pigeons, and various pies).

Still cheap in America

Yet across the ocean, because lobster meat in our relatively unfished ocean was so plentiful, it would become the main protein fed to prisoners, apprentices, and slaves.

Another unfortunate lobster fact: As Protestants, local Maine historians might have seen regular fish dinners as an imposition of Catholic practices. So lobster meat suffered a double whammy; it was both common and vaguely sacrilegious.

When canning arrived in the 1840s, Maine became dotted with canneries. Canned lobster was cheap. As late as the 1850s, when Boston baked beans sold for 53 cents a pound, canned lobster sold for just 11 cents a pound.

When restaurants first started to serve lobster in the 1850s and '60s, it was a bargain dish in the salad section, like pickles or cottage cheese, and cost half the price of chicken salad.

At first canneries boiled only lobsters between three and six pounds, discarding smaller lobsters. But over only a decade, fishing became so aggressive the lobsters didn't live long enough to grow that size. Canneries began to go out of business when the cost of shelling outweighed profits.

Lobster facts: The first Renaissance

In the 1870s, the well-to-do from New York and the city of Washington had begun traveling to New England shores escaping the summer heat. Local cooks in Maine discovered that a one- or two-pound lobster nicely fit the plate.

Back home, the well-to-do, having picked up a taste for boiled lobster, were ready to pay for live lobsters that, with the advent of refrigeration and ice packing, could now be shipped south to their restaurants, and as far west as Chicago and St. Louis.

At the same time, the railways had begun spreading through the nation. It turned out that passengers from the inland, who found lobster exotic, loved it. Lobster was delicious!

It helped that by the 1880s chefs had discovered that lobster looked and tasted better if it was cooked live. In the first Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, in 1896, the index lists: Lobster bisque, chowder, creamed, croquettes, curried, cutlets, devilled, plain, salad, sauce, scalloped, soup, and stewed.

Prices began to soar, nearly quadrupling in the 1890s. Maine lobstermen worked harder and harder, but the catch fell.

Only rising prices kept them in business. As is the case today, restaurants, not home cooks, most often served lobster. A turn-of-the century restaurant in New York, founded in 1908 by two Italians, is said to have served three primary dishes: minestrone soup, chicken, and lobster fra diavolo, the spicy tomato dish.

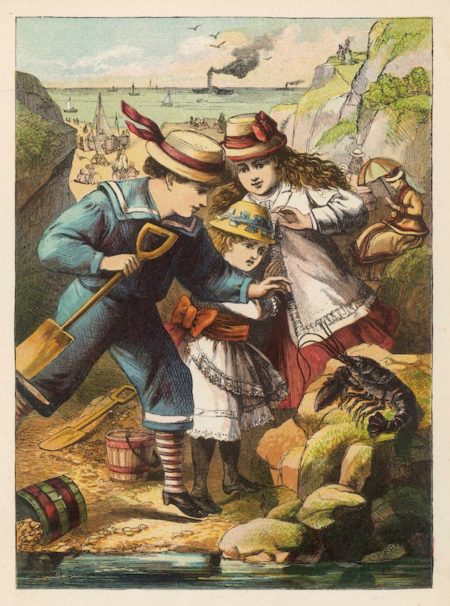

Lobsters became so linked to luxury that by the end of the century, a wealthy, desirable single man (think Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice) might be called a "lobster." Fanciful drawings on postcards showed a lady trying to catch a well-dressed "lobster" as a mate.

Prices fall and rise again

In the 1920s, lobster prices peaked. Then there was another reversal during the Great Depression, when the luxury clientele dried up and prices fell. By World War II, soldiers sat in foxholes in France eating canned lobster. In that time, some Canadians remember children trading lobster sandwiches for peanut butter and jelly in the school cafeteria.

Conservation laws allowed the lobster population to slowly build back up. The market recovered, and by the 1950s lobster had regained its high status. A midtown Manhattan restaurant called The Flying Lobster advertised on its menu that it flew lobsters directly from Maine on its own plane.

Nowadays, lobster is fit for the king of movie stars: George Clooney's foodie wedding included lemon risotto with lobster as a main course.

5 lobster facts you didn't know

- The largest American lobster on record weighed 44 pounds and may have been 100 years old. Lobsters on average live 50 years.

- Lobster shells still make great fertilizer! They'll add calcium, phosphates, and magnesium to your compost.

- Lobsters, like human beings, tend to favor one front limb. They can be right- or left-clawed.

- A lobster's brain resides in its throat, nervous system in its abdomen, kidneys in its head, and teeth in its stomach. It hears with its legs and tastes with its feet.

- Lobster meat is less caloric than the same portion of skinless chicken breast, while containing omega-3 fatty acids (a four-ounce tail contains about 40 mg), potassium, and the vitamins E, B-12, and B-6.

It seems unlikely that this delicious and now comparatively scarce dish will ever again lose its stellar culinary reputation.