Life began in water, an idea we seem to have understood long before science explained evolution.

Why else did fish symbolize fertility in so many ancient cultures, from Egypt to the Celts, Indians, Mesopotamians, Burmese, Persians and Slavs?

Through the centuries — beginning more than 14,000 years ago — fish continued to carry sacred meanings when they appeared in visual art.

A fish scratched in the ground was an early Christian signal. It became a symbol of baptism, our immersion in water.

But the image of a fish is multidimensional, straddling sacred, secular and, of course, even culinary worlds. It can tell a very different story about the human experience.

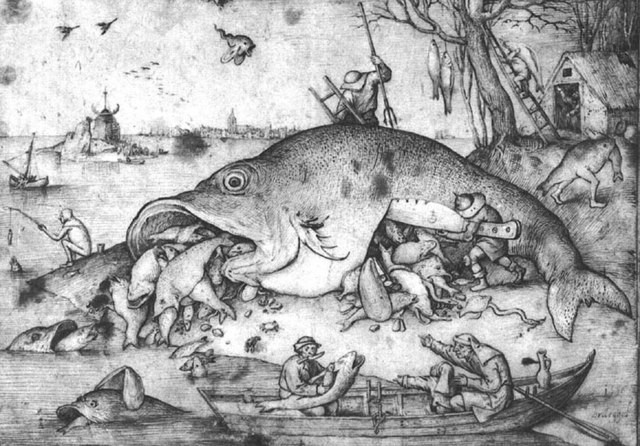

In 1557, a print in the style of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, for example, made a political point. It illustrated an ancient Latin proverb, “The Big Fish Eat the Little Fish," demonstrating how the powerful rule society.

Not long after, Guiseppe Arcimboldo, sometimes called the great-grandfather of surrealism, gave us a haunting allegory about the power of “Water" in a face made up of fish.

Fish appeared in the first still-life paintings, in compositions of richly laden tables, serving as symbols of both abundance and piety. At the time, the Catholic church and custom insisted on meatless days as often as three days a week, so fish was frequently on the menu.

Fish pictured as food is generally raw. That's probably because the colors are more vivid and varied than in a cooked fish.

An example from the early 17th century comes from Flemish still-life specialist Clara Peeters. Her depictions of feasts sometimes suggested domestic drama — will the house cat take a bite?

Another example of fish symbolizing household abundance is from none other than Vincent van Gogh. His 1886 “Still Life with Mackerel, Lemon and Tomato" is the image at the top of this article (Vincent van Gogh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

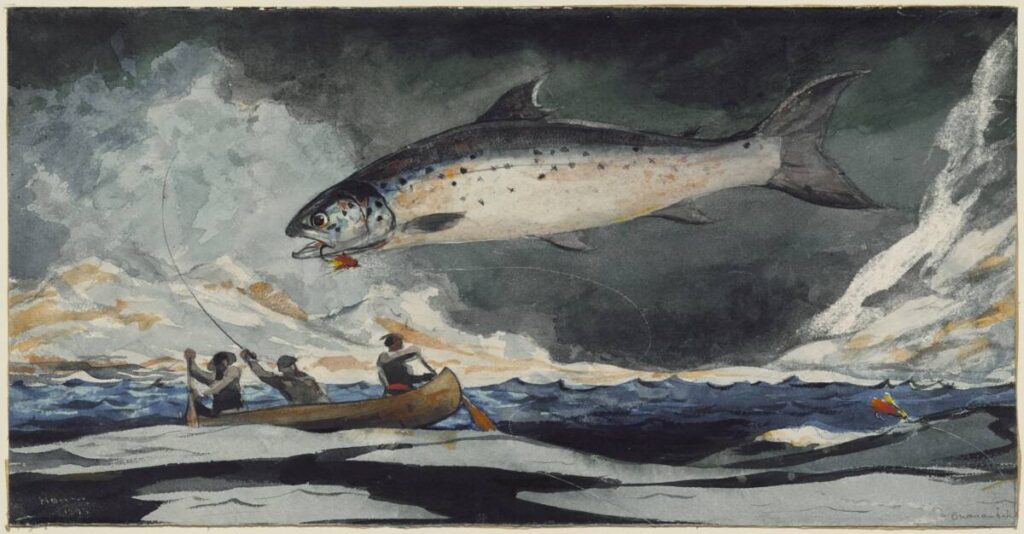

Allegory seems always lurking in the background even in modern depictions of fish. For example, when an enormous fish soars above three men in a canoe, in Winslow Homer's 1895 classic “A good pool, Sagueney River" the scene is reminiscent of Moby Dick, the story of a man obsessed with taking revenge against an immense whale.

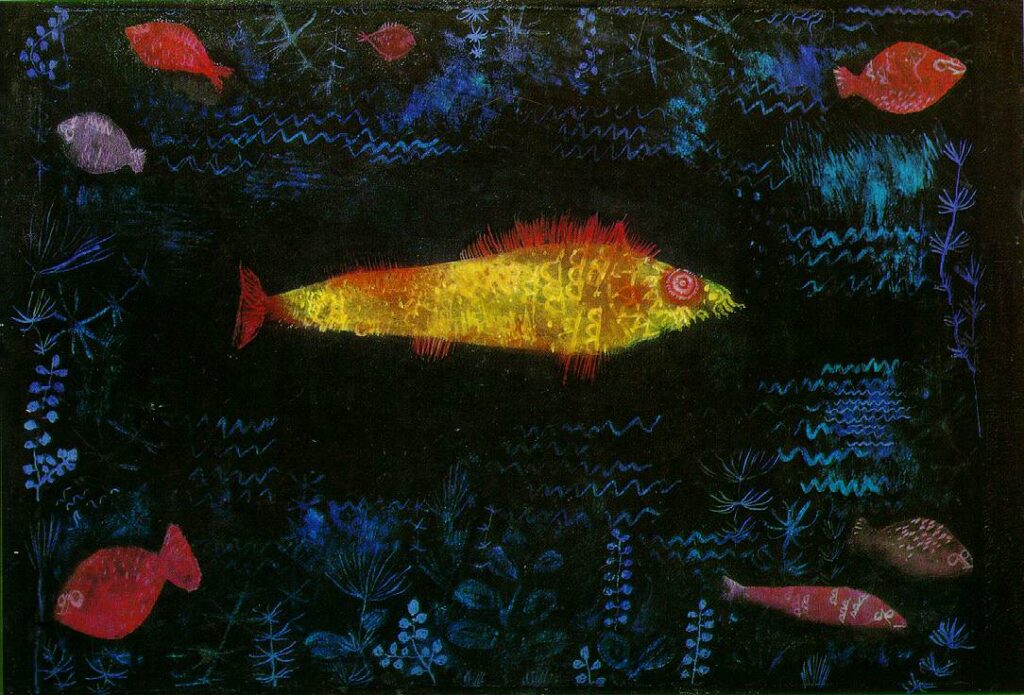

In Paul Klee's “The Goldfish," painted in 1925, the body of the fish contains scratchy shapes that suggest the early Christian symbol. The overall fish is greatly simplified, as if symbolic. Have we come full circle?

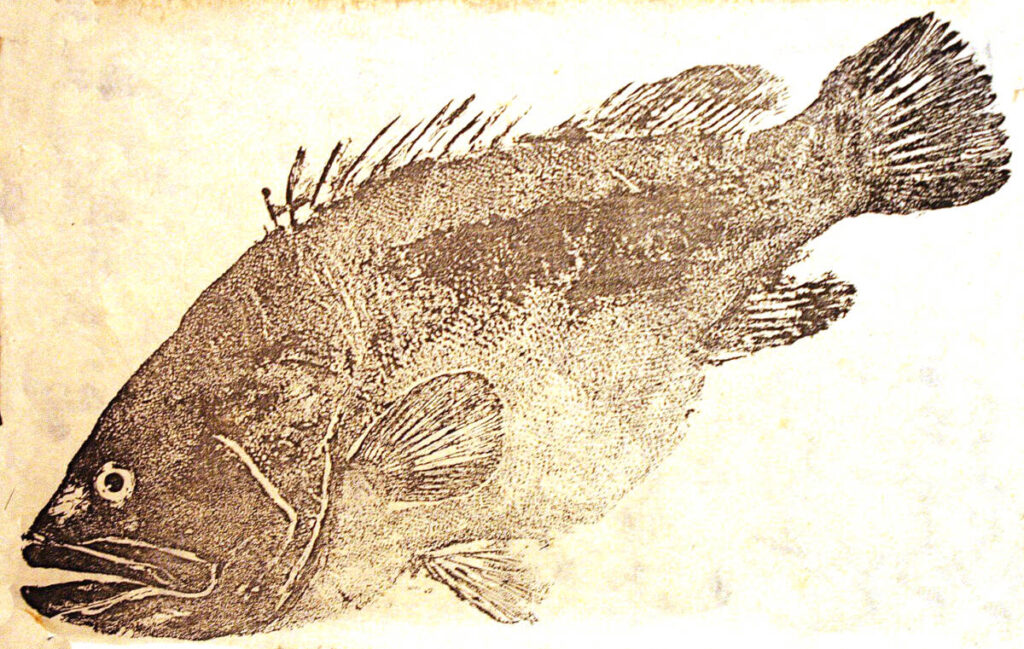

Even when they don't directly represent divinity, politics, or material abundance, fish are simply beautiful in their own essence. We see this in the most realistic renderings of all, in a technique that began in Japan in the mid-1800s known as gyotaku. "Gyo" is “fish" and “taku" means “rubbing." Anglers kept rice paper, ink, and brushes on their boats so that they could make ink etchings of their fresh catch, brag about its size and perhaps marvel at its splendor.

Today, artists sometimes put ink on a fish body and press silk or rice paper on top. Or they might put paper on the body and then apply the ink. They then paint in the eyes and other details to create stunning underwater worlds.

Inhabitants of a world obscure and mysterious to us, yet the one in which our distant ancestors were born, often beautiful, essential to human thriving and believed a locus of miracles, fish are to the artist, as to all of us, myriad glorious things at once.

May we continue to appreciate them in their many-splendored beauty!