The First Thanksgiving: Mussels and More

The first Thanksgiving feast featured seafood, and there's no reason to avoid it now.

Nov 25, 2024

History buffs, want to mix it up and make your Thanksgiving meal more accurate? Then don't forget the lobster. Four hundred years ago, the bounty of seafood in Cape Cod Bay and nearby rivers would help feed the new hungry arrivals in Plimouth, Massachusetts. Our traditional Thanksgiving array of turkey and buttery high-carb sides came centuries later.

The first Thanksgiving was more like a Maine shore seafood bake.

What the first colonists ate

To match what the colonists and the Wampanoag most likely ate at harvest time in 1621 Plimouth, you could be serving passenger pigeon, swan, goose, or duck rather than turkey.

Actually, whipping up a passenger pigeon roast would present a serious challenge, as they are now extinct. In the pioneer days, they were so abundant you could hear them before you saw them, and they darkened the sky.

In any case, seafood was prominent, and fortunately all species the pioneers ate still swim in the sea. You might be serving eels, lobster, clams, and mussels along with some other kind of smoked fish, historians say.

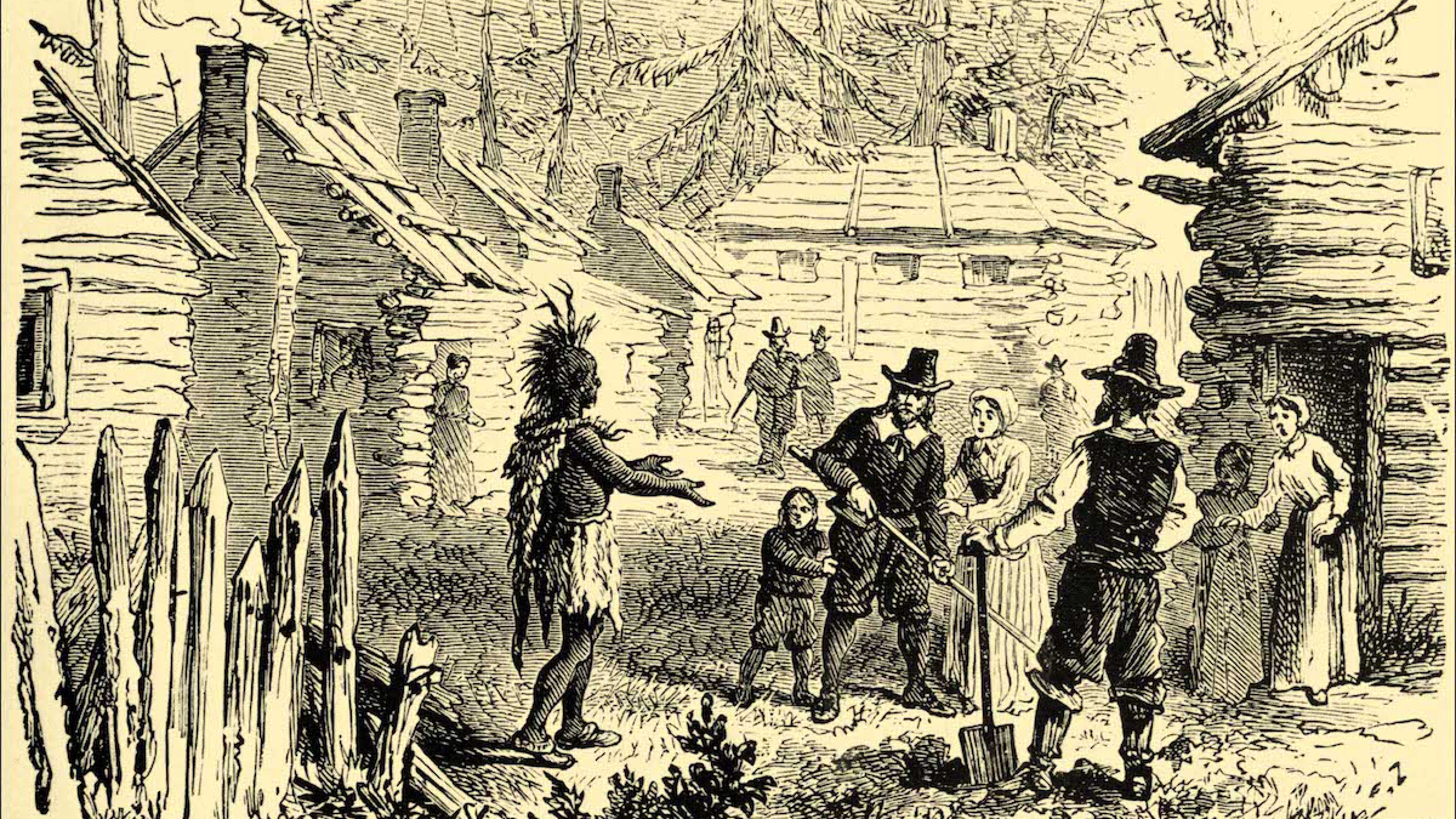

History of the first Thanksgiving

At the museum celebrating the Plimouth settlement, the regularly sold-out and historically accurate “New England Harvest Feast" includes “Mussels Seeth'd with Parsley and Beer" as a first course and “Fricassee of Fish" as a second, alongside corn pudding, "Stew'd Pompion" (archaic English for pumpkin), and roast pork.

Deer was also on the 1621 menu, a gift from the Wampanoag described in a letter from Edward Winslow, a guest, along with local "fowl." That was most likely goose, duck, or pigeon. Birds were stuffed with chunks of onion and herbs or chestnuts, not bread.

Cookbooks, descriptions of gardens, and archaeological remains provide other clues. The sides in the original meal would have been drawn from the staples that fed the Wampanoag, who ate chestnuts, walnuts, and beechnuts from the forest; multicolored Indian corn; green beans; pumpkins; and squash.

They helped the colonists plant gardens, which are later described as containing turnips, carrots, garlic, and pumpkins. White potatoes (from South America) and sweet potatoes (from the Caribbean) hadn't made it north, and cranberry sauce didn't appear for another half-century.

The all-important river

The Town Brook, the colony's main source of fresh water, enticed the first colonizers. The Mayflower landed in Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, which didn't supply enough fresh water for these British to make an essential: beer.

When they rounded the tip of the Cape and sailed across the bay, though, they spied the brook on the mainland. It emptied into a salt marsh suitable for anchoring boats. Not far away was — you guessed it — a big rock.

Silvery river herring swam upstream in Town Brook. Squanto, the famous guide, taught the newcomers to layer dead herring as fertilizer with their corn seed, producing the multicolored crop.

The brook also supplied eels and waterfowl that flocked to a pond they called Billington Sea, and Squanto taught the colonizers how to trample eels out of the mud.

The woman who invented Thanksgiving

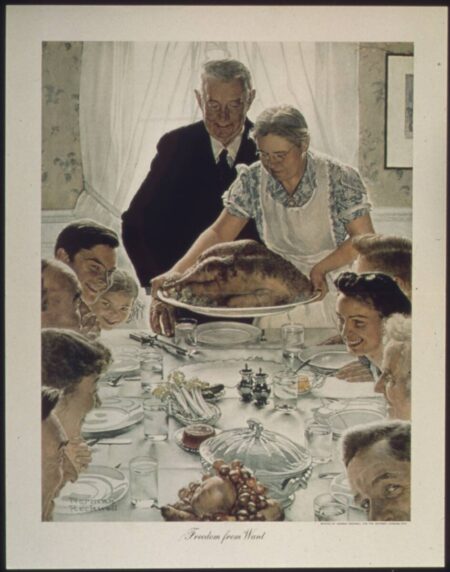

So how did we get to today's feast? As you sit down to your family's celebration, your history lesson by rights should include the woman who started the modern version of the pioneer feast.

Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the popular women's magazine 'Godey's Lady's Book,' petitioned presidents for more than 30 years to establish a harvest holiday. In 1863, President Lincoln made Thanksgiving a national holiday to unite a country divided by the Civil War.

Hale put recipes and menus for her new holiday in her magazine and many cookbooks, establishing traditions like sage dressing and creamed onions. Mashed potato, still new to American palates, appeared, too.

By the 1880s, exotic macaroni had arrived on Victorian Thanksgiving tables. However, their macaroni and cheese dish — unlike the soul food favorite once called “macaroni pie" — included tomato and was more like what we'd call lasagna.

Which just goes to show that Thanksgiving meals aren't set forever; rather, they evolve as part of our cultural history. Perhaps your family would go for lobster bisque or lobster steamed in beer, two New England favorites? A bit of herring in honor of the all-important fertilizer? Eel from your local Korean market? The sky's the limit…though I wouldn't try cooking a swan.

READ MORE: Thanksgiving Fish Recipes

Lobster steamed in beer

Use about two cans of beer (not light beer) for 7½ pounds of lobster.

Have two sticks of butter, two whole lemons, and sea salt handy.

Start with an inch of water in your pot, or an inch of beer. Either way, add two tablespoons of sea salt. Add your beer.

Bring the liquid to a rolling boil over high heat.

Add lobster, cover tightly, and wait until the water is boiling again (yes, you'll have to take a peek under the lid) before you begin timing. After seven minutes, stir the lobster to move the tails at the bottom to the top. When done, the lobster shell will be bright red.

Serve with melted butter and lemon wedges.

Fricassee of Fish

"Fricassee" is the French word for stew. The meat is prepared separately from a white sauce.

In honor of our Plimouth diners, you might choose cod (Vital Choice's bits and pieces option works, as you'll be breaking up the fish anyway). But you can add any fish your family enjoys.

Bring lightly salted water to a simmer. Add cod and cook for about eight minutes. Save the water.

You can prepare vegetables like peas, green beans, or mushrooms separately to make sure they aren't under- or overcooked.

Also separately, you'll make a classic French roux. You'll need a tablespoon of butter and flour and a half cup of milk for every pound of fish.

Melt the butter, whisk in flour until the mixture is smooth, then add a bit of your cod cooking liquid, again stirring so there are no lumps. Gradually add more liquid until the sauce is too thick, then add your milk.

Finally, add the fish and vegetables then season with salt, pepper, and lemon juice. Put a sprig of parsley on the plate or on top.

It's really quite simple, but it can look fancy!